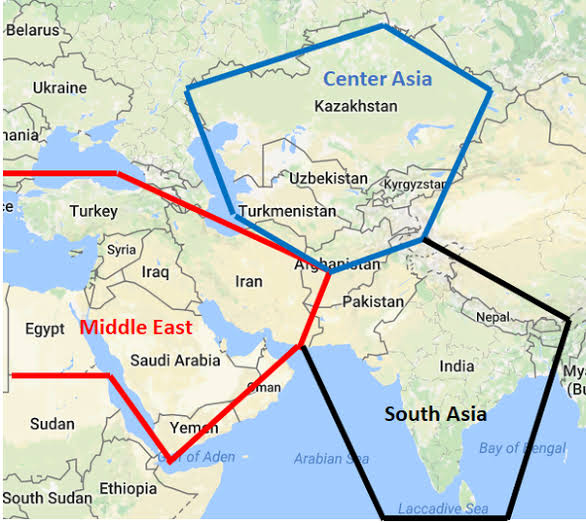

In Central Asia-South Asia Connectivity, no South Asia without India

By Aditi Bhaduri, The Quint

Last week the US announced the formation of a new “QUAD” – which includes the Central Asian country of Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and of course the USA for “Regional Support for Afghanistan-Peace Process and Post Settlement.” A statement issued by the US State Department said that the four countries had agreed “in principle to establish a new quadrilateral diplomatic platform focused on enhancing regional connectivity. The parties consider long-term peace and stability in Afghanistan critical to regional connectivity and agree that peace and regional connectivity are mutually reinforcing. Recognizing the historic opportunity to open flourishing interregional trade routes, the parties intend to cooperate to expand trade, build transit links, and strengthen business-to-business ties.”

Afghanistan’s vantage geographical location as the “roundabout”, connecting Central and South Asia has long been acknowledged and in order to strengthen her economy, taking advantage of this factor, the US has pushed similar initiatives earlier too. For instance, the earlier administration of Barack Obama had created the C5+1 – the five Central Asian republics (CARS) and the US.

Afghanistan shares its longest border of 2,800 km with Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. This proximity, along with historical and cultural linkages, makes the CARs a direct stakeholder in Afghanistan’s peace and stability. Given Afghanistan potential as a lucrative transit country to the markets of South and Southeast Asia a number of initiatives like the CASA 1000, the Heart of Asia process, Regional Economic Cooperation Conference on Afghanistan, the Lapiz Lazuri Route and others have been floated. At least fifty per cent of Afghanistan’s trade in 2019 was with it’s CARS neighbours.

Stabilising the Afghan economy and integrating it into the regional economy would go a long way in stabilising the country. At the same time the CARS are all landlocked countries with enormous reserves of natural resources. Connectivity through Afghanistan and Pakistan are particularly seductive for them.

In fact the “Quad” was floated on the sidelines of a high level conference on Central Asia-South Asia Connectivity that the double landlocked country of Uzbekistan hosted in its capital Tashkent. A key component of the conference was Afghanistan, with President Ashraf Ghani attending the conference.

Uzbekistan is one of Central Asia’s most powerful and the most populous state. Connectivity, therefore, acquires even greater salience, for it, with exiit to the warm waters of the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean gaining priority, as it would cut down time and cost, logistically more beneficial to transport goods to South and Southeast Asia and the Middle East. That explains why Uzbekistan is expending considerable effort in forging connectivity partnerships along different routes but especially to South Asia.

Uzbekistan is implementing projects like has Khairaton Mazari-Sharif railroad, and the Surkhan Puli-Khumri electric power transmission line are being implemented. Talks are now on for extending railway lines from Mazar-e Sharif through Kabul in Afghanistan to Peshawar.

At the Tashkent conference Pakistani premier Imran Khan participated – only one of the two heads of government. In its search for connectivity Uzbekistan is seeking to deepen cooperation with Pakistan. The latter too is interested in finding markets in Central Asia and through Central Asia further into Russian federation and Europe. The Central Asian region offers an estimated $90 billion market.

The Pakistani economy is cash strapping and struggling. The pandemic has further dented it. The much touted China Pakistan Economic Corridor which ptomised big gains has run into trouble with major differences appearing between Islamabad and it’s all weather friend China.

In Tashkent, Khan said “Pakistan has immense potential to connect Central Asia with rest of the world and become a hub of trade.”

But think South Asia and the largest market is India. India also offers shortest routes to the markets of Southeast Asia.

As of 2020, with $2,709 bn, India’s GDP is around ten times higher than Pakistan’s gdp of $263 bn. In nominal terms, the gap is wider (above ten times) than ppp terms (8.3 times). India is the 5th largest economy in the world today.

For Pakistan allowing transit trade to and from India to Central Asia would earn it billions of dollars.

At the Tashkent conference Imran Khan did make a reference to this, but conditioned it to the settlement of the Kashmir issue. Earlier this year too Khan had made a reference to the possibility of allowing India trade access to Central Asia through Pakistan, soon after both India and Pakistan had announced the resumption of the cease-fire on the Line of Control. But linking transit rights to India to the resolution of the Kashmir issue flies in the face of Khan’s own much harped policy of moving on from ‘geo-politics’ to ‘geo-econimics’.

India has not been invited to join the new quadrilateral. The ability and importance of India’s trade with Afghanistan can be gauged from the fact that the Chabahar port project in Iran was exempted from US sanctions. India and Afghanistan have been making use of the Chabahar port and have also opened up an air freight corridor. Even Uzbekistan has joined the Chabahar port project with the first Trilateral Working Group Meeting between India, Iran and Uzbekistan on the joint use of the port held virtually on December 14, 2020. India also has started making use of the Russian initiated North-South Transport Corridor.Missing out from it is Pakistan with it’s obdurate refusal to allow India transit rights through its territory.

Of course, the situation in Afghanistan will have to be stabilized before all these grand plans can be realised. But that is also one of the objectives of all these initiatives. Money flowing in as transit fees will be an immense incentive to whoever controls the territory to ensure safety and security of the trade routes.

The Central Asian countries know that the shortest route to market’s of South Asia (India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan) is through Gwadar and Karachi ports. And the most coveted market in the region is that of India’s, which would also offer shortest connectivity to the markets of Southeast Asia. Without India’s participation, therefore, connectivity and trade would remain limited to Central Asia and Pakistan, but it certainly wouldn’t be Central Asia-South Asia trade.