‘Mismatch’ between government aid and places modern slavery exists: New UN data tool

A new interactive data tool created by the UN University Centre for Policy Research, which shows a mismatch between where modern slavery occurs, and where governments are spending resources to address it, could help make a positive impact on policy debates surrounding the issue.

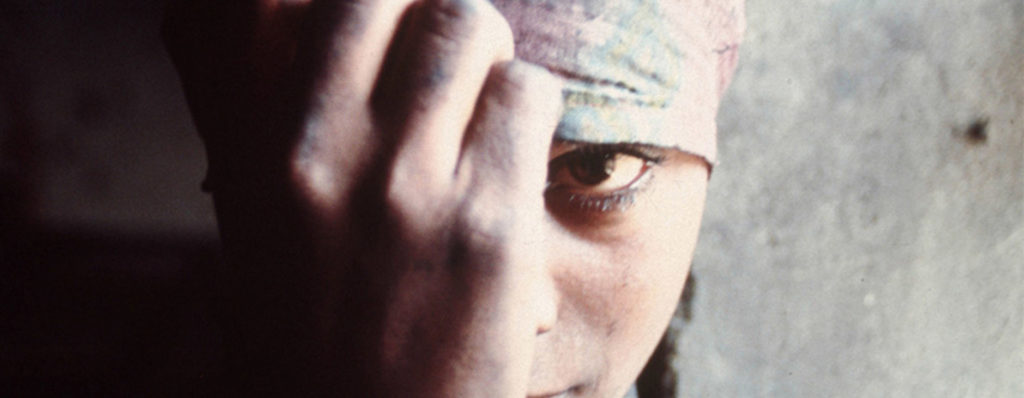

Photo: ILO/A.Khemka

The release of Modern Slavery Data Stories, a series of easily understandable animated graphics, provides detailed pictures of the ways that factors related to modern slavery have changed over time, and comes during a period when over 40 million people are living in slavery, more than ever before in human history.

UN-led research shows that half of those enslaved are victims of forced labour in industries such as farming, mining and domestic service, while the rest are victims of sex slavery, forced marriage slavery and child slavery. According to the latest Global Slavery Index, published by the Walk Free Foundation, the three countries with the highest prevalence of modern slavery are North Korea, Eritrea and Burundi.

Breaking down the complex story of modern slavery

Modern Slavery Data Stories are developed by Delta8.7. an innovative project from the United Nations University’s Centre for Policy Research, in collaboration with technologists from the prestigious Carnegie Mellon University in the US, to help policy makers understand and use data, in order to create effective legislation. In an exclusive interview with UN News, Dr. James Cockayne, Director of the Centre for Policy Research, and head of Delta 8.7, says that eradicating slavery by 2030 would require freeing around 9,000 people every day, a rate far higher than that currently being achieved.

Modern slavery is a product of the way our global political and economic system works. It is a feature, not a bug.

– Dr. James Cockayne, Director, United Nations University Centre for Policy Research

One of the ways to get there, says Dr. Cockayne, is to break down this complex phenomenon and present it in ways that influential non-experts can comprehend. Because data on these subjects has been so patchy, he says, this story has been difficult to tell, so Delta 8.7 built a machine-learning algorithm, which scoured official aid programme descriptions to figure out which countries committed how much, to tackle which forms of exploitation, when and where. This is how his team discovered the mismatch between where modern slavery occurs, and where governments are spending resources to address it: “That kind of insight, made obvious through these powerful visuals, can have a real impact on policy debates.”

Slavery: a feature of global society

For Dr. Cockayne, the key thing that has been learned from analysis of the data, has been that modern slavery is actually a product of the way the global political and economic system works: “it is a feature, not a bug.”

As the Global Slavery Index shows, many of the products we take for granted, including mobile phones, computers and cars; as well as clothes, cosmetics and even food, are produced using raw materials extracted by people living in a state of slavery.

Solutions, therefore, will have to be system-wide, involving all elements of society, from the technology industry to the global financial sector. “Partnerships are key.” And modern slavery victims, he says, must form a part of the process, because “Without their voices informing research, programming and strategy, we risk not only being ineffective, but actually doing further harm.”

Sustainable Development Goal 8: decent work for all

The ambition to eradicate modern slavery by 2030 forms part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, a pathway to eradicating poverty and achieving sustainable development, which was adopted by all the UN Member States in 2015. Goal 8 calls for the “promotion of sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all,” and it contains several targets and indicators, one of which, Target 8.7, is to take “immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms.”

Looking forward, as the data and evidence gathered through Delta 8.7 helps to build up an informed understanding of what is working, the project will feed research into an upcoming report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery, Ms. Urmila Bhoola, which will be delivered to the Human Rights Council later this year.