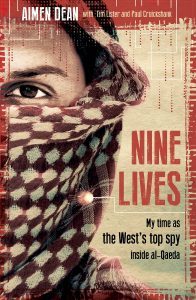

Nine Lives: My Time as the West’s Top Spy Inside Al-Qaeda

Book Review

By Kyle Orton

The main issue with that Nine Lives has to overcome is the one that has attended Aimen Dean (a pseudonym) since he went public in March 2015 with an interview he gave to the BBC, claiming he had been a British spy within Al-Qaeda between 1998 and 2006. That issue is overcoming the doubts about his story. Nine Lives goes a long way to solving this by bringing in Paul Cruickshank, the editor-in-chief of CTC Sentinel, one of the premier academic resources in the terrorism field, and Tim Lister, a terrorism-focused journalist with CNN, as co-authors. As well as helping structure the book from Dean’s memories, the two co-authors note they had been able to “corroborate key details” that convinced them: “In the years immediately leading up to and following 9/11, Aimen Dean was by far the most important spy the West had inside al-Qaeda”.

The Origins

Dean was born in late 1978 to a Bahraini family that resided in the town of Khobar in Saudi Arabia amidst the event that he identifies as the take-off point for the modern wave of Islamist radicalism, namely the Iranian revolution. In January 1979, the Shah of Iran, unwilling to engage in mass-killing to suppress the “Islamist-led protests”, as Dean notes, departed his country, and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, credulously believed by many Westerners to be a Gandhian figure, was swept to power, inaugurating a bloodletting that has never ended. This was the beginning of a tumultuous year that “changed our religion and our politics forever”, says Dean.

The theocracy that took hold in Iran was Shi’a, exciting people in the area Dean lived, the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia—hence his kunya later, Abu Abbas al-Sharqi (Abu Abbas the Easterner). But that sectarian dimension was not so pronounced at the time and the Sunni radicals were as emboldened as their Shi’a counterparts by the birth of an Islamist state. Ayman al-Zawahiri, the current leader of Al-Qaeda, was a specific case, as Dean points out.

Throughout 1979, there were other events that fed the nascent jihadi cause: the intensified Islamization of Pakistan under General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq and the extension of increasing levels of support to Islamists in Afghanistan; the seizure of the Haram Mosque in Mecca, which surrounds the holiest site in Islam, the Ka’ba, by Juhayman al-Utaybi’s apocalyptic cult; and the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel that was seen as the final proof of the impiety of Anwar al-Sadat’s regime in Cairo. (“I have killed Pharaoh”, said Sadat’s assassin, Khalid al-Islambuli, referring to the pre-Islamic rulers of Egypt.) And then came the next key event, connected to the first.

In December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, seeing it as the only solution to issues that were largely in the imagination of the KGB. The first KGB conspiracy theory earlier in the year saw the Soviet client regime in Kabul as preparing to “do a Sadat on us” by taking Afghanistan into the Western camp. By the time of the invasion, the Centre had come to believe, spooked by the Islamist revolution in Iran, that it was possible Afghan dictator Hafizullah Amin was going to cut a deal with the Mujahideen insurgents to create an Islamist regime, and this in turn would create a contagion of instability domestically in the Muslim-majority Soviet republics of Central Asia. The Red Army’s brutal occupation of the country over the next nine years brought in the Arab jihadists, including Al-Zawahiri and Usama bin Ladin, and with them connections and money that made Al-Qaeda possible in the 1990s.

Becoming a Radical

Dean came to his radical interpretation of Islam as part of the Sahwa (Awakening) stream of opposition politics in Saudi Arabia in the early 1990s. Dean was part of a study group, the Islamic Awareness Circle, where among his first lessons was to stop watching the Smurfs cartoon because it was “a Western plot to destroy the fabric of our society”. The group disdained the ilmiya (scholarly, often misleadingly called quietest,) version of Salafism as a “royalist” heresy, believing it to be essentially a tribal construction in religious garb to protect the House of Saud. “My friends and mentors were gravitating towards a more politically active interpretation, best exemplified by the Muslim Brotherhood’s involvement in social work and discreet political activism”, says Dean, and he became “immersed” in the works of Brotherhood ideologue Sayyid Qutb and his brother, Muhammad.

In October 1994, while a sympathiser of the Islamist revolts in Algeria and Egypt but “still some way from being a revolutionary” himself, a 16-year-old Dean went to Bosnia with three others, including his friend Khalid Ali al-Hajj (Abu Hazim al-Sha’ir), a Yemeni who had already fought in Afghanistan and by late 2003 the leader of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the insurgent force when jihad came home to the Saudi Kingdom. After a brush with the devil’s temptation at the Vienna airport—Dean had to swap seats with Khalid because of a young lady in a sleeveless dress—and some logistical issues that diverted them to Slovenia, the foursome arrived through the well-worn Dubrovnik-to-Bosnia route.

Dean gives a glimpse of the way he thought while within the jihadist universe. Eating French fries at a diner on the way to Bosnia, Khalid asked, “How do you want to die?” Describing his reaction to this morbid question, Dean says: “The discussion energized rather than depressed us. That’s why we had made the journey: to offer our lives for the cause.”

In Bosnia, the quartet went to Zenica, one of the epicentres of the jihadists who had migrated to the country to assist the government in its war against the Croat Catholic and Serbian Orthodox militias that were supported from Zagreb and Belgrade, respectively. Many of the Islamist militants were from Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ), Al-Zawahiri’s outfit, which was then-engaged in a death struggle with the Egyptian government and would go on to officially merge with Al-Qaeda just before 9/11.

The globalist vision of Al-Qaeda was taking shape in Bosnia. Qutb’s teachings were being used not only to mobilise fighters locally—they were in Dean’s mind when he charged toward the Serbs’ guns, and had to stop to administer morphine to a wounded comrade—but they were being interpreted to license transnational revolution, to excommunicate the Arab rulers, for example, including the Saudi royal family, something that was at that time unthinkable to him and most jihadists.

The other factor in Bosnia that helped Al-Qaeda go truly global was Iran, but Dean unfortunately does not pursue this dimension, despite so clearly noting that it was the advent of the Islamic Republic that started it all. During the Bosnian war, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) trained and led most of the Islamist militants, and its Intelligence Ministry virtually took over the Bosnian security sector. The only mentions Dean makes of Iran’s role in collaborating with Al-Qaeda are a “growing apprehension that Iran was becoming a logistical hub for al-Qaeda” after 2003, and finding out that the replacement for Al-Qaeda’s external operations chief, Khaled Shaykh Muhammad (KSM), after his arrest in Pakistan, was Hamza Rabia and he was based in Iran. It’s a notable lacuna in the book, albeit one explainable by it not being in Dean’s immediate purview.

The Wandering Jihadist

As the Bosnian war wound down, Dean looked to Chechnya, but was unable to get there and wound up in Afghanistan at the infamous Darunta camp. Dean describes the spartan, dreary life in Afghanistan—dividing a Mars bar among five on the rare occasion they could get hold of them—and yet the feeling was one of satisfaction, that they were the vanguard to lead the way towards God’s design.

From there, Dean went with Khalid to fight for the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) in the Philippines, getting moved into first class on the Kuwaiti flight and taken to meet the captain when the air marshal turned out to have lost a brother in their jihadi unit in Bosnia. As Dean says, “Nowadays we would both have been on Interpol’s Red Notice and US no-fly lists.” Dean’s romantic notion of a jungle jihad on behalf of oppressed Muslims was no to be. “In the course of seven months,” he says, “I was at greater risk of dying from snakebite than in a kinetic encounter.” Though, in fact, he did get injured by shrapnel from a mortar shell and was returned to Afghanistan.

The move to Afghanistan took Dean through Pakistan and a safehouse run by Zayn al-Abidin Husayn, the Al-Qaeda operative who became known to the world as “Abu Zubaydah”. Dean was back in Afghanistan barely a month when he was asked to take his bay’a (oath of allegiance) to Bin Ladin personally, which he did in Kandahar in September 1997.

Dean was induced to take this oath, and to work with Al-Qaeda “central”, rather than on the jihadi “fronts”, by Abu Hamza al-Ghamdi, using a pitch that was eschatological in nature; he was told “the age of the final prophecies” was upon the world and Al-Qaeda was to be the “Mahdi’s army-in-waiting”. Such apocalyptic ideas recur throughout Dean’s experience with Al-Qaeda, something that runs counter to a lot of the accounts of the group, which portray its leaders as aristocrats scornful of such superstition.

Dean was now rubbing shoulders with Al-Qaeda’s most senior officials like Muhammad Atef (Abu Hafs al-Masri), the operational manager of Al-Qaeda and one of the few men to know about 9/11 in advance, and tried his hand as a bomb-maker, and with chemical and biological weapons, at Darunta, working under Midhat Mursi al-Sayid Umar (Abu Khabab al-Masri).

This brought forth feelings of unease for Dean, and the August 1998 attack on the U.S.’s East African Embassies was the final straw. Dean believed the Qur’an forbid suicide, and he had been strongly opposed to EIJ’s November 1995 suicide attack on the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad, judging that Al-Zawahiri’s men had crossed a line. The massacre of hundreds of Africans, many of them Muslims, for the sake of a dozen Americans was something Dean could not justify.

Leaving Jihadism

Dean had gotten malaria earlier in Afghanistan and had it treated in Qatar. In late 1998, on the pretext of getting a medical follow-up, Dean travels to Doha, where he intends “to get out, disappear”. But Dean is picked up by Qatari intelligence, and, after informing them of Abu Zubaydah’s role in providing passports to the network behind the Metro attacks in Paris and several other pieces of information that check out, it is accepted that he has changed sides.

After nine days of “courteous but insistent questioning”, Dean is given the choice of where to be sent: France, America, or Britain. Dean explains:

I had a whole half-hour in which to decide the rest of my life.

I felt little cultural affinity for the French and didn’t speak the language. I didn’t trust the Americans either, and, given my lingering anger over the Dayton Accords, the idea of talking to them was a step too far. I imagined (was it the spy films?) that the British were more professional than other intelligence agencies. They understood the Arab world; they had been here long enough. I had enjoyed being in London when I had picked up the satellite phone.

There was another reason. My grandfather had fought against the Ottomans for the British in the Mesopotamia campaign of the First World War. He had risen to the rank of major and become head of the Colonial Police in the Iraqi city of Basra. He had always spoken of British administration in glowing terms.

After my appointed half-hour was up, I was ushered back into the colonel’s office.

“I’m ready to go to London,” I said.

After a nervous stopover in Bahrain, where Dean is a wanted man, because the U.S.-U.K Operation DESERT FOX against Saddam Husayn has closed down the airspace over the Gulf, Dean lands in Britain in December 1998.

Dean is formally run by for the British foreign intelligence agency, the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, often known as MI6), but works closely with domestic security, MI5, as well. One of the first disclosures Dean makes to the British is that Mustafa Kamel Mustafa (Abu Hamza al-Masri), the hook-handed leader of Finsbury Park Mosque and by then a well-known figure to the security services, is providing funding to the Darunta camp through his son. Dean tells the intelligence officers of plans for kidnappings and attacks on churches in Yemen, and also hands over disks disclosing Abu Khabab’s plans for mass-casualty atrocities. Five British jihadists are arrested in Yemen on 23 December 1998, which averts the terror attacks, though sixteen tourists, including twelve British citizens, are kidnapped five days later.

Life in Londonistan

One of the most fascinating parts of the book is the cast of characters Dean interacts with, and after his debriefing, Dean is set loose as an agent of the British government into the London Islamist scene of 1999 that was, as one White House counterterrorism official put it, “the Star Wars bar scene” of jihad—a concentration of dangerous radicals with few rivals anywhere in the world.

Ali al-Fakheri (Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi), the head of Khalden camp in Afghanistan, contacted Dean to put him in touch with Said Arif, the head of Al-Qaeda’s intelligence apparatus in London and the deputy to Umar Othman (Abu Qatada al-Filistini), one of Al-Qaeda’s most senior clerics to this day, who in 1999 was raising lots of money in Britain that was being devoted to jihadi causes around the world. Othman might have become the relative “moderate”, but in the mid-1990s it was under fatwas bearing his name that the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) had engaged in a strategy of wholesale massacre in Algeria.

Othman and Mustafa did not get along; Othman resented that Mustafa had the larger platform despite being a theological novice, and Mustafa resented that despite his larger platform the prominent Salafis in the Middle East and elsewhere paid more attention to Othman. These petty personal rivalries recur time and again, such as between Atef and Mustafa Setmariam Nasar (Abu Musab al-Suri). Jihadists are human, too.

The final prominent preacher on the London scene is Umar Bakri Muhammad, a Syrian founder of Hizb-ut-Tahrir, who carried much less theological weight than the other two, though much more physical weight. All three—Othman, Mustafa, and Muhammad—were capable of raising money for nefarious ends, and did so.

Dean is set up in a modest apartment on Brighton Road, in Purley, South London, and earned a wage from “working part-time in an Islamic bookshop, topped up by a £1,500 monthly stipend from Her Majesty’s Exchequer.” His flat became a “dormitory” for jihadists moving through the city, and was wired up by the security services so that his visitors could be listened to.

Dean highlights a major problem of those years: if jihadists confined their operations inside Britain to fundraising, they were left largely unmolested. (By some accounts, this was a semi-formal pact between the jihadists and a state more concerned about nuclear proliferation risks from the fallen Soviet Union and Northern Ireland.) As Dean puts it:

I was rapidly getting the sense that MI5 was ill-equipped to deal with the panorama of jihadi agitation across London (and also in places like Birmingham, Luton and Manchester). The resources and focus were elsewhere, and the counter-terrorism laws were much weaker than they would be after 9/11. The law before the turn of the century made it difficult to prosecute anyone not actively planning an attack on British soil. Asylum laws were generous; extradition both difficult and time-consuming. Jihadis flocked to London from all over Europe and North Africa, knowing that arrest was unlikely so long as they did not announce plans to bomb Piccadilly Circus.

Return to Afghanistan and September 11

In June 1999, under the cover of setting up a honey business for Al-Qaeda, Dean returns to Afghanistan, this time as a British agent. He is taught how to spot when he is under suspicion, how to read facial cues, and how to evade awkward questions—primarily by sticking as closely as possible to the truth.

Upon return to Afghanistan, Dean finds that Abu Khabab has developed a new chemical mix for suicide bombs, based on TATP, which is then used by the Palestinian terrorists during the Second Intifada. The Taliban convey a message to Australia through Dean that it will keep the groups under their regime from attacking the Sydney Olympics in September 2000 as a way of trying to gain some international goodwill. And in June 2001, Dean is sent to Britain with instructions from Atef to stay there until further notice and to send four senior Al-Qaeda figures to Afghanistan before the end of August because “something big” is coming.

Dean and his British handlers “had guessed that [‘something big’] might be another embassy attack or the bombing of a US military facility in Europe. The idea that al-Qaeda was planning to hijack and crash multiple aircraft into the towers of the World Trade Center, the US Capitol and the Pentagon was beyond our wildest imagination and our worst fears.” As Dean notes, short of being recruited to the 9/11 conspiracy there is little he could have done to find out about it: its architect, KSM, had kept it compartmentalized from most of the senior leadership of Al-Qaeda and even many of the hijackers only found out what their mission was properly shortly before the attacks.

At one point in 2002, Dean finds himself headed back to Bahrain, where he will end up spying on his brother, and a British intelligence officer is sent to vet Dean to find out whether “family or firm” will win-out. After going over Dean’s life history thus far—he is only 24 at this stage—the officer asks:

“Do you have anyone you can confide in—a partner? Have you ever had one?”

I could tell he was fishing.

“No – my career path sort of precluded that.”

He could tell from my tone, which verged on scornful, that he had struck a nerve. The discipline required of being a jihadi and then a spy had helped me deal with both temptation and the melancholy of being single, but the truth was that I badly wanted a companion with whom to plan a life.

“Has it occurred to you that you might be stifling your sexuality?” I wasn’t ready for that and reacted angrily.

“Oh great,” I said. “I’m about to depart for a mission that’s not exactly risk-free, and you want me to think about whether I’m gay. Sure, I come from a culture where men and women simply don’t mix, where sexuality is repressed, but looking at the birth rate they do apparently get together at some point. And one day, I will leap at the chance if the right woman comes along. It will also be my last day working for British intelligence.”

I couldn’t tell whether [the officer] thought my protests a little too loud. But he laughed and swiftly changed the subject.

Apart from being darkly comic, this episode highlights one of the questions a reader is left with about the book: completed in early 2018, can he really remember an interaction in this level of detail from sixteen years ago? Perhaps one would believe this of a handful of emotionally-charged incidents, but even in the heightened emotional state that must attend being a spy and with Dean’s “photographic memory”, one is given to wonder about a full book of such incidents recounted at this depth.

Still, it is believable Dean would remember—and it is something that the co-authors can check—that Dean’s intelligence led to the arrest of Bassam Bokhowa and his co-conspirators in February 2003 as they headed across the causeway from Saudi Arabia to Bahrain with a laptop containing plans for al-mubtakkar (the invention), a device created with Dean’s input at Abu Khabab’s camp that would have released chemical weapons on the New York subway.

The subway operation had been sanctioned by the leader of AQAP, based in the deserts of the Saudi interior, a man named Yusuf al-Ayeri (Sayf al-Battar), who had warned Dean of the dangers of the Smurfs all those years earlier. But the plot had been called off already by Al-Zawahiri because he worried that such an attack would be used to justify the invasion of Iraq, which was then weeks away, by ostensibly demonstrating that Saddam had given weapons of mass destruction (WMD) to Al-Qaeda.

As the insurgency got underway in Iraq, it was a Jordanian brute for whom Dean had once interpreted a dream in Afghanistan, Ahmad al-Khalayleh (Abu Musab al-Zarqawi), the founder of the Islamic State (ISIS), who came to the fore as its leader, with a little help from the Saddam regime that ceded tens of millions of dollars—at a minimum—from the central bank to Zarqawi on literally the eve of the invasion. And after Al-Ayeri’s demise, it was Khalid al-Hajj, Dean’s old friend, who took over AQAP and the Saudi Islamist insurgency.

When Khalid was killed in March 2004, Dean was in Bahrain, and after giving a eulogy for his friend to a circle of Al-Qaeda loyalists, found himself confronted with Turki al-Binali, then-19, who became one of the most visible ISIS clerics a decade later and issued the ISIS fatwa calling for Dean to be killed. Al-Binali denigrated the mujahideen who went to Bosnia since it “was not a jihad to establish God’s sovereignty over Earth.” Dean says that there is a religious duty to “sav[e] Muslim lives”. Al-Binali will not have it, and Dean concludes that he was an “arrogant sociopath”. Dean says he was vindicated by events and one tends to agree.

The End of the Road

After helping dismantle the AQAP network inside the Saudi Kingdom—with Riyadh able to push the group into Yemen, where it still is—Dean was returned to Britain after being arrested in Bahrain; the Americans had demanded the government move too early against a plot Dean had infiltrated, and most of the terrorists walked free for lack of evidence.

Back in the U.K., Dean re-entered the domestic jihadi scene, finding the spreading influence of Anwar al-Awlaki, another jihadi preacher who found the Brotherhood icon Sayyid Qutb to be ideologically inspirational. Dean helped thwart a plot involving the use of pure nicotine as a poison and was at work on 7 July 2005, when Al-Qaeda bombed the London transport system. Two of the killers, Mohammad Sidique Khan and Shehzad Tanweer, had been peripherally noticed during surveillance of a previously uncovered terrorist cell, “but had not been judged priority targets”.

Doubts about British intelligence’s handling of its assets creep in after an ill-fated plan to smuggle a gun to Kenneth Bigley, the Liverpudlian taken captive by Zarqawi’s group, is given the go-ahead, failing to save Bigley, who is beheaded on a video by Zarqawi in October 2004, and leading to the murder of SIS’s prize asset within ISIS’s predecessor.

In June 2006, these doubts were realised when Dean’s time as a British agent came to an abrupt end. Details of the 2003 New York subway plot, appearing in Ron Suskind’s book, The One Percent Doctrine, were published as excerpts in Time Magazine, and gave enough identifying information about the informant within Al-Qaeda to compromise Dean.

Dean fumes at his SIS handlers for being unable to protect such an important source, but he knew they were not responsible, that a “bigger play [was] going on. The British liked to show the US they punched above their weight, still brought gold to the table, still knew how to deploy and gather human intelligence better than anyone. In the process, they shared information that was thrown into the roulette wheel of leaks and spin for which the US government was notorious.”

The book is ordered by Dean’s nine “lives”, his various missions and brushes with death, and the final one is the saddest: his favourite nephew takes up with the jihadists in Syria, where he is killed, aged 19, in September 2013, and Dean journeys to his grave in Saraqib. Already at that moment he can see the way the trend is going. The rebels he meets are local people resisting a cruel regime and its foreign supporters, particularly Iran and its Shi’a jihadists. But this localism and the lack of coherent ideology, while providing a certain geographic resilience for a time, meant that as the war was allowed to protract it was the extremists with a dogma—the derivatives of Al-Qaeda, ISIS, Iran’s IRGC, and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)—who could keep men on the battlefield.

Conclusion

After an engrossing contribution that is essentially unique in the annals of jihadist literature and one with few rivals in the espionage field, Dean offers some concluding thoughts, particularly lamenting that the ideology behind Al-Qaeda and ISIS will live on, with the works of Al-Binali and Zarqawi’s mentor, Muhammad Ibrahim al-Saghir (Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir), widely available.

There is little to argue with in Dean’s conclusion that drone strikes and raids will not be enough against jihadism, nor that a more humane political settlement and sectarian reconciliation in the region will be needed to drain the fuel away from the jihadists. His contention that moderate Islamists and anti-jihadist Salafists are allies in this struggle is more controversial. Dean encourages efforts to get competing narratives onto the jihadists’ favoured platforms like Telegram.

“We should aid those with even a sliver of doubt”, Dean writes, and perhaps denting the certainty, human and historical, that leads into jihadism, creating and disseminating material that might provoke just enough hesitation, is in the end about all that really can be done.

Nine Lives: My Time as the West’s Top Spy Inside Al-Qaeda

Aimen Dean, Paul Cruickshank, and Tim Lister; Oneworld Publication;

2019; 432 pages

(The author is an independent researcher. The article originally appeared here.)