Protracted Conflict and Local Neutral Arbitration

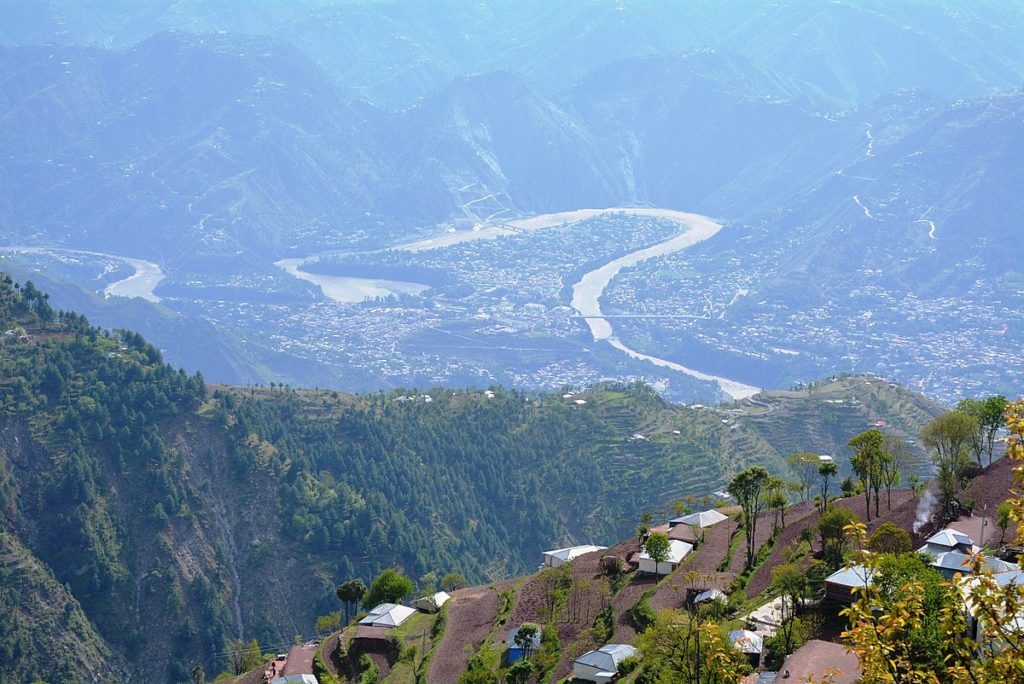

Tanveer AhmedThe view from Muzzafarabad

Photo: Wikimedia/Creative Commons Attribution

It has been a few years since I have interacted with Indian media and have meaningful memories of my experience. We all have our conceptions and compulsions. We all fight bad with good in our own way of understanding the world. We all prefer peace and progress to anarchy and impairment.

Every well-intentioned idea deserves a hearing and an audience.

In contrast, since my arrival in this territory in 2005, I have never been invited by any Pakistani media – print or electronic – to submit my opinion on any matter whatsoever.

To my utter disadvantage, I have found that Pakistanis don’t take sweet talk seriously. I have always got the impression that they feel that to be their exclusive privilege. In most cases that I have experienced, anybody who genuinely wants to give them honest and pleasant advice receives a response – almost by default – that they think the advice they are receiving has some hidden intent. They may even fear that somebody else will benefit at their expense.

Conversely I have found them to respond more attentively to criticism – however well founded – even more so if you abuse them and possibly furthermore if you physically fight them, although I don’t have much experience of the latter.

Apart from matters at the LOC and a suffocation of anything that doesn’t glorify Pakistan and curse India in equal measure, everything else here in Pakistan administered Kashmir, which Pakistan likes to call Azaad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) is almost tolerable. We enjoy relative peace compared to the Valley, Gilgit Baltistan (GB) and even Jammu at times. For most citizens though, it is the peace of a graveyard. Curiosity and creativity are killed here at first sight.

I don’t want to be so certain about my version of the Indian psyche, if indeed there is such a thing given the country’s size and diversity. That is because apart from a few winter months in 1989 (aged 17) and a few summer months in 1993, my experience of India is far less than that of Pakistan. It would be folly to compare and avoiding partisanship towards any of our neighbours is our strategic stance.

In any case, I want to converge on the main points that I want to make but that foreground was necessary.

I hasten to add that criticising Pakistan does not necessarily indicate bias towards India and likewise criticism of India does not necessarily indicate a bias towards Pakistan. Indeed, from the perspective of an aspiring citizen of an un-divided Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), learning of an historical precedent in the centre of Europe in 1515 AD, convinced me many years ago that the J & K conflict has its best chance of being resolved, if the inhabitants of this territory commit their ‘contested’ State to neutrality.

The Swiss may have politically evolved a few hundred years before us and their neighbours may have learned many a lesson from past conflicts with each other but this digital age combined with the increasing likelihood that the 21st century will be an Asian century, gives many of us hope that Jammu & Kashmir can emerge as a neutral secular confederation of States, enabled by direct democracy to convert the autocratic structure of the Dogra Raj. The barriers to what many may still dismiss as an outlandish idea are only political will on the part of India and Pakistan. Having said that, admittedly this neutral approach needs to be inculcated deeper and practiced more measurably by the inhabitants of J & K.

It should be pointed out – not least for posterity’s sake – that the idea of a neutral J & K is not a novel idea. It was what the last Maharajah Hari Singh wanted. Indeed it is what his main internal political foes leading up to the British transfer of power in 1947 also claimed to desire, once they fell out of favour with India and Pakistan respectively, namely Shaikh Abdullah and Sardar Ibrahim. On the 11th of May 1999, the idea was presented at the Kashmir Panel of the UN Hague Appeal for Peace Conference. On the 22nd of August 2003, it was even discussed in an editorial of a prominent Indian newspaper entitled, “Zurich on the Jhelum”. That very same paper had interviewed the current prime minister of Pakistan prior to that editorial. Imran Khan was also convinced that a neutral Kashmir was the only solution to this protracted conflict.

When two countries have been at conflict for so long, it is more than likely that they are both wrong at some level. As inhabitants of Jammu & Kashmir, we cannot all fit into either of those binary narratives. Bilateralism hasn’t delivered. Many consider the conflict to be a well developed industry bringing dividends from sporadic warfare. Thus, opening up the possibility of returning the responsibility of resolution to the affectees will generate a vested interest in peace.

Ideological bias usually based on religious affinity may help drum up various quarters on either side of the LOC but that only serves to entrench divergent narratives even deeper, which in turn increase the misery and helplessness of the innocent inhabitants. Every military conflagration by India or Pakistan destroys years of patient peace-building and meticulous narrative bridging on our part, as indigenous civil society.

Many people have written on events preceding the British partition of India and many more have monitored the political history of Indian-administered Kashmir and Pakistani-administered Kashmir since 1947. While heavy introspection of each country’s approach is needed, there is also much work to be done by the citizens of Jammu & Kashmir. Conflict resolution cannot be a static master plan drawn up in a cosy room. It is a series of rigorously thought-out improvised processes over time; that take account of all strands of opinion and regional concerns.

Despite the traditionally fierce resistance of both India and Pakistan to cede territory to each other, they have both been even more determined to prevent an independent path for the territory they are alleged to covet. Indeed, various clauses in the Simla Agreement (clause 6 for example) have been interpreted as a tacit agreement by both countries to forestall the possibility of independence.

“Both governments will take all steps within their power to prevent hostile propaganda directed against each other. Both countries will encourage the dissemination of such information as would promote the development of friendly relations between them.”

In almost 14 years of an un-interrupted presence in this territory whereby most of my time has been utilised in activism and research on the ground, including visits to all parts of the erstwhile princely State bar Ladakh, I have also been privy to discussions between various Indian and Pakistani citizens with decades of experience in back-door diplomacy between the two countries.

The Indian approach on account of it controlling the relatively elevated share of water resources (exemplified in the Indus Basin Water Treaty of 1960), controlling the historically coveted Vale of Kashmir, being determined to hold onto its only Muslim majority State in a secular India and perhaps most important of all ensuring that whatever India controls does not fall into the lap of Pakistan; are all serious factors from an Indian point of view. Thus, it is understood that India would like the status quo to become a permanent geo-political feature and hence it has always (or certainly since the 1960s) advocated for the Line of Control (LOC) to become an international border. Consequent to which it says, that it would open up the region to more natural cross LOC movement and economic opportunities.

The Pakistani approach has always been heavily invested in championing the 2 nation theory and what they describe as the unfinished agenda of partition. They have devoted most of their energy on trying to equate Pakistan with Islamic honour and valour, even to the extent of making their whole population undergo wholesale sociological experimentation to calibrate them with the Pakistani nationalist narrative. This has come at great cost to Pakistani society and there is little economic benefit to the masses living in a conflict-driven economy. It hasn’t helped the Valley of Kashmir either, to put it mildly.

Both approaches are at opposite ends of the spectrum and continually repeating what has proved wrong over decades only exacerbates the dilemma for all people concerned. These relationships between India, Jammu & Kashmir and Pakistan need to be re-invented. That isn’t likely if both countries insist on us abiding by what we perceive to be statist narratives.

Military demilitarisation cannot be wished away but it can be incremental, beginning at subdivision (tehsil) level. Indeed, since 2012 we have been urging the Pakistanis to take the initiative – as prescribed by the UN, as suggested by our cleanest and brainiest politician ever to come to power in AJK namely K H Khursheed; as judged from the prism of economic, diplomatic and military clout of India compared to Pakistan and not least because Pakistan advocates the issue as one of self-determination. If you are keener on a solution compared to your adversary, then you would appropriately be more open to suggestions and flexibility.

We have identified tehsil Khuiratta in district Kotli to be that first subdivision for demilitarisation. The procedure and contingency required to maintain peace are open to discussion and would be formalised upon political will emerging. If such a step were to stabilise one relatively small portion of the LOC then we could make a similar suggestion to the Indian government to do likewise in a similar sized subdivision in the Valley, where the conflict between both countries is most intense, on a day to day level.

In such an improvised scenario, all stakeholders would see merit in maintaining the peace and this gradual subdivision by subdivision demilitarisation approach would enable the viability of peace dividends incrementally.

There is much more to elaborate, qualify and substantiate in due course but I would also prefer to treat this as a dynamic process, not a static event.

Some aspects need dedicated attention in their own right. Amongst them connectivity is key to a shared future and prosperous and peaceful Jammu and Kashmir and for confidence building between India and Pakistan so that their resources can be diverted towards more pressing needs, mainly poverty alleviation in a region rife with illiteracy and poverty.

(Tanveer Ahmad is an independent researcher and public policy activist in Muzzafarabad, Pakistan-administered Jammu and Kashmir. The views are the author’s own. The International Affairs Review neither endorses nor is responsible for the same)

A perfect analysis by Tanveer Ahmed with a word of wisdom: “NEUTRALITY.” Any victim who takes sides, only damages their case.

Thanks for the excellent article

Thanks, it is very informative

Thanks, it is very informative

Thanks for the great guide

Thanks for the terrific post

This is actually helpful, thanks.

Incredible points. Solid arguments. Keep up the amazing effort.

Keep working ,remarkable job!

I like this post, enjoyed this one thank you for putting up. “No trumpets sound when the important decisions of our life are made. Destiny is made known silently.” by Agnes de Mille.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. After all I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!